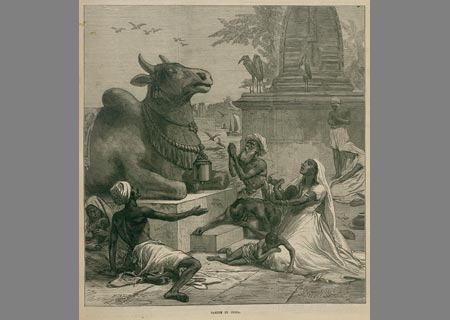

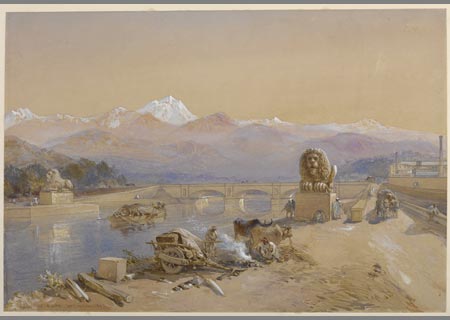

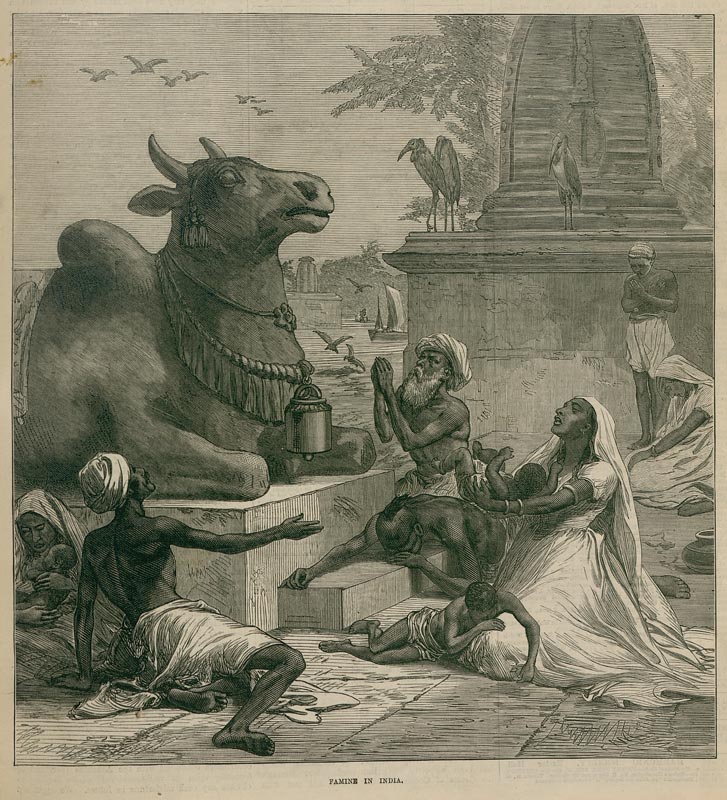

“Hear the Tale of the Famine Year”: Famine Policy, Oral Traditions, and the Recalcitrant Voice of the Colonized in Nineteenth-Century India

- Volume 31, Number 1

- Gloria Goodwin Raheja

- View PDF | Download PDF

- http://journal.oraltradition.org/issues/31i/raheja

Abstract

This essay considers the appearance of British colonial representations of Indian oral traditions in administrative documents concerning famine relief policies, as an example of the connection between colonial ethnography on the one hand and forms of disciplinary control on the other. Raheja analyzes eleven Hindi and Punjabi famine songs recorded in colonial texts, songs that addressed issues of hunger, famine, “custom,” and famine policy in tones of either compliance or critique. The singers of these songs occupied various locations within local hierarchies and with respect to the colonial state; she reads their words as historically situated, reflective, heterogeneous, and diversely positioned memory and critique. Raheja argues that while compliant native voices in a few of these songs were characterized as “the voice of the people” and entextualized in colonial documents to create an illusion of Indian consent to colonial rule, other voices–the voices of remonstrance and lament–were erased or marginalized or criminalized, to contribute to that same illusion.

eCompanion